This post is going to look a little different because, well… the week looked a little different. About 12 inches of snow different.

Monday and Tuesday disappeared thanks to winter weather, and Wednesday through Friday were all late starts. So instead of our usual rhythm, we had a shortened, stop-and-start week right as we were beginning our Constitution unit. Not ideal timing, but sometimes you just roll with what you get and adjust on the fly.

Wednesday

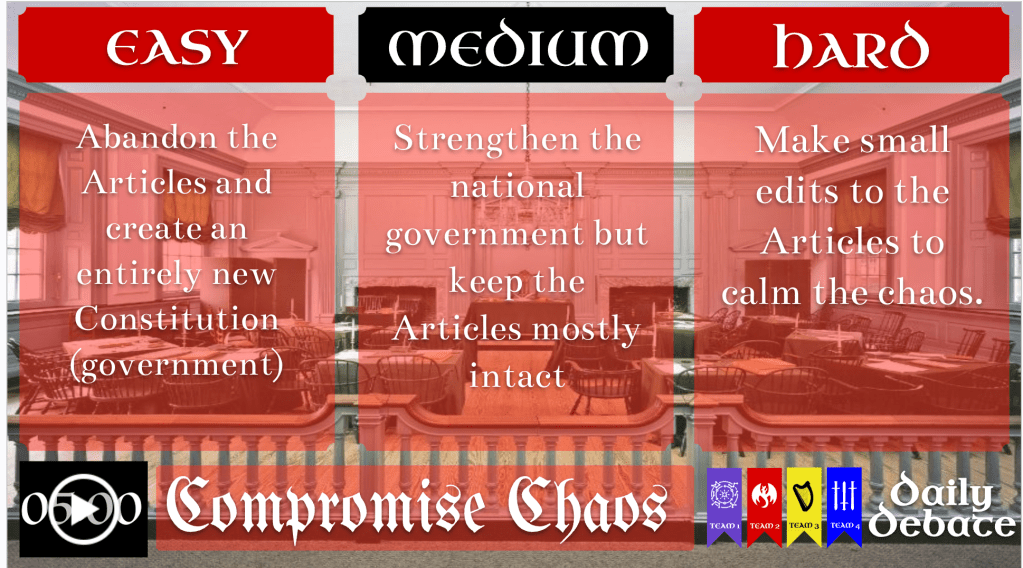

We officially kicked off the Constitution unit Wednesday. Normally, I teach Federalists and Anti-Federalists right after the Constitutional Convention, but this year I’m trying something different. We’re going to move through the principles of government first and then circle back to those debates later. We’ll see how it goes. Sometimes changing the order helps ideas click better, and sometimes it just teaches me what not to do next year. Either way, it’s worth trying.

To get us started, I used questions pulled from the U.S. citizenship test focused on principles of government. I asked ten questions out loud and told students the goal was six correct answers, just like the traditional citizenship test requirement.

I also told them that the test changed this past year. Now there are 128 questions, some are worded in confusing ways, and several feel unnecessarily political or outdated in language. One thing I noticed was the repeated use of the word “alien,” which is outdated and dehumanizing. The new version also asks twenty questions instead of ten and requires twelve correct answers to pass.

So for classroom purposes, we stuck with the old format. Ten questions, six correct to pass. Clean, simple, and it gets the conversation started without bogging things down.

Thursday and Friday

Because of late starts, I saw half my classes Thursday and the other half Friday, so both days followed the same plan.

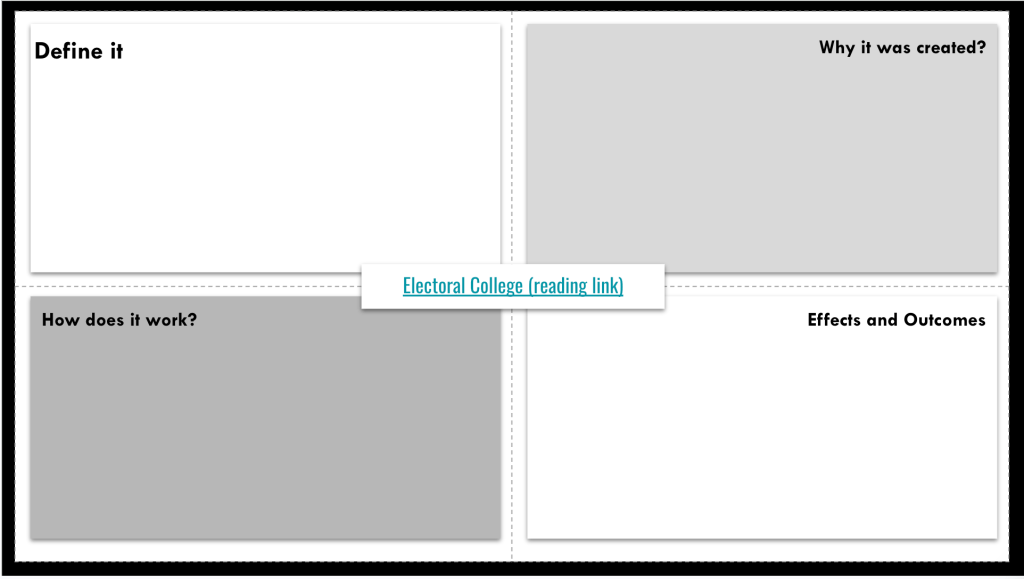

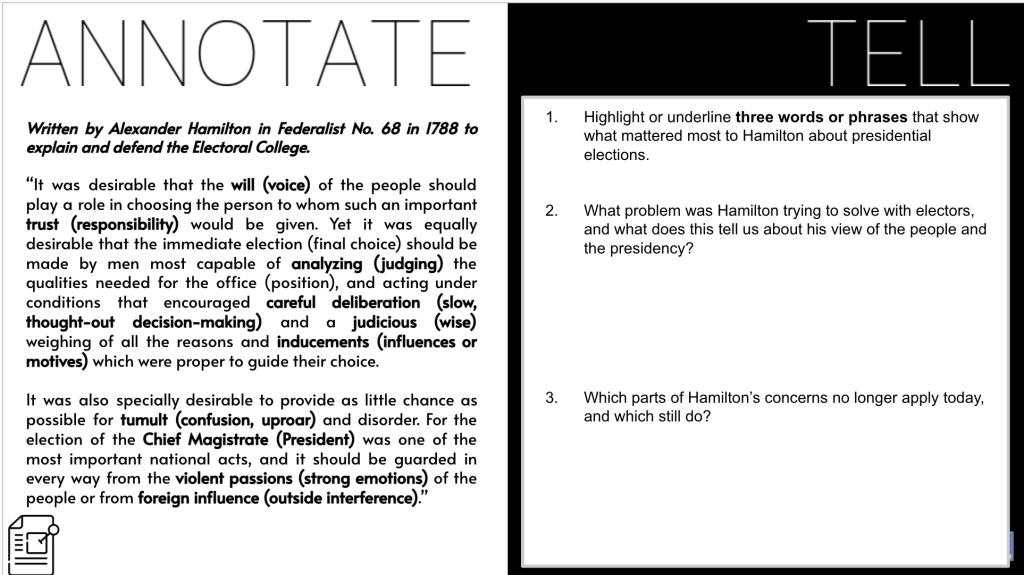

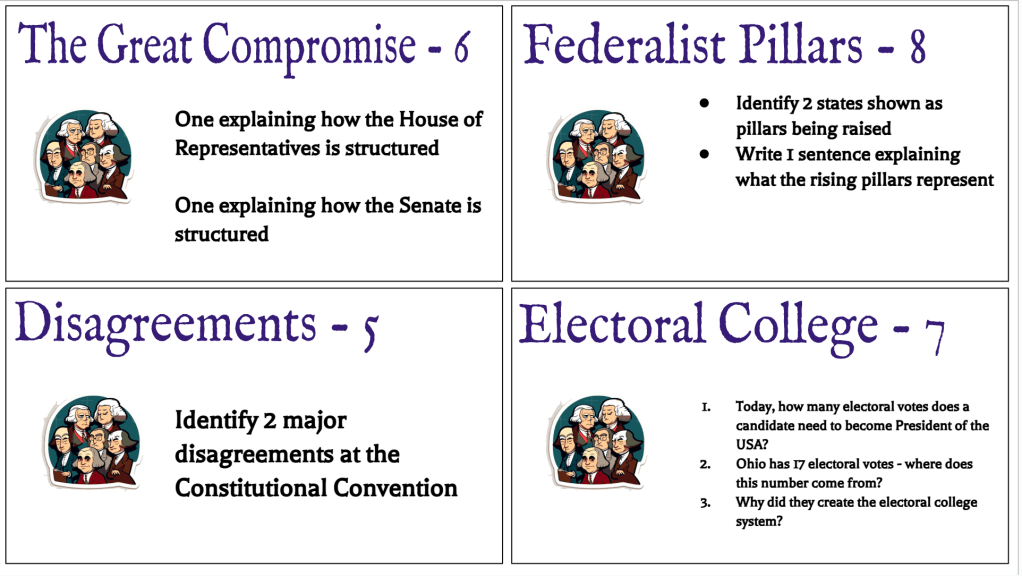

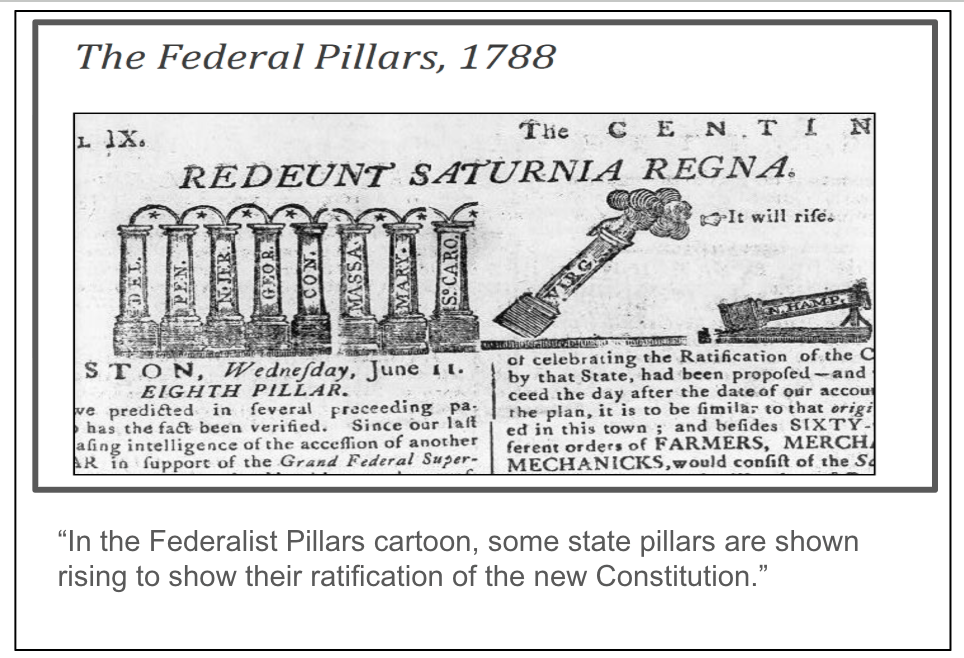

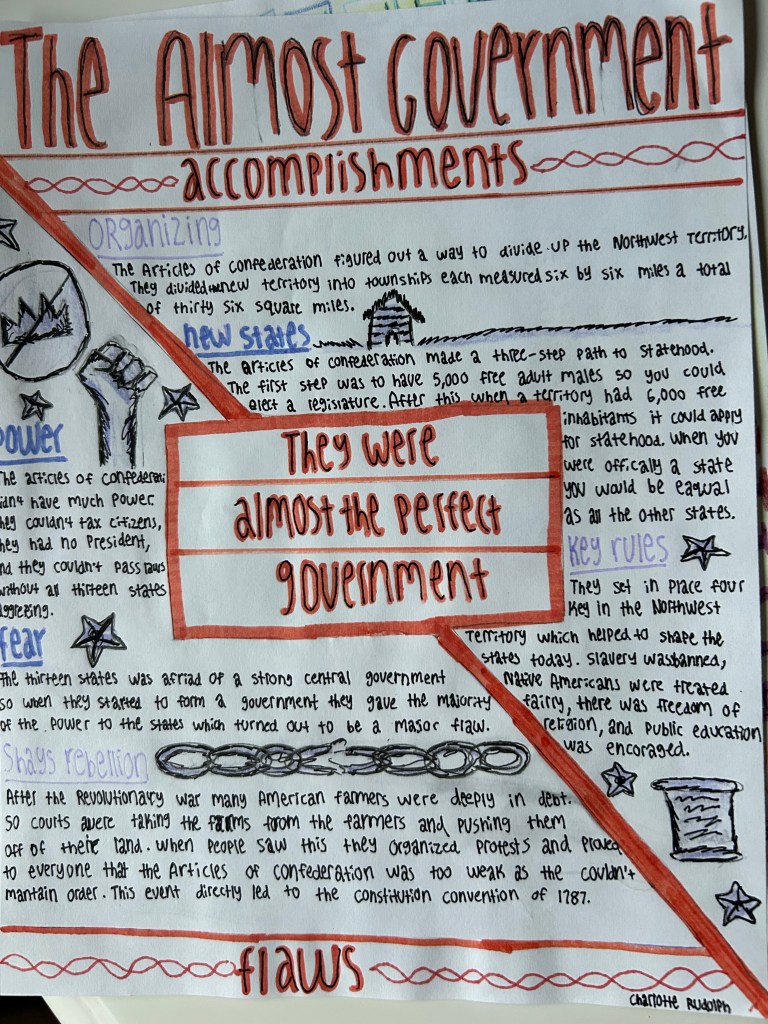

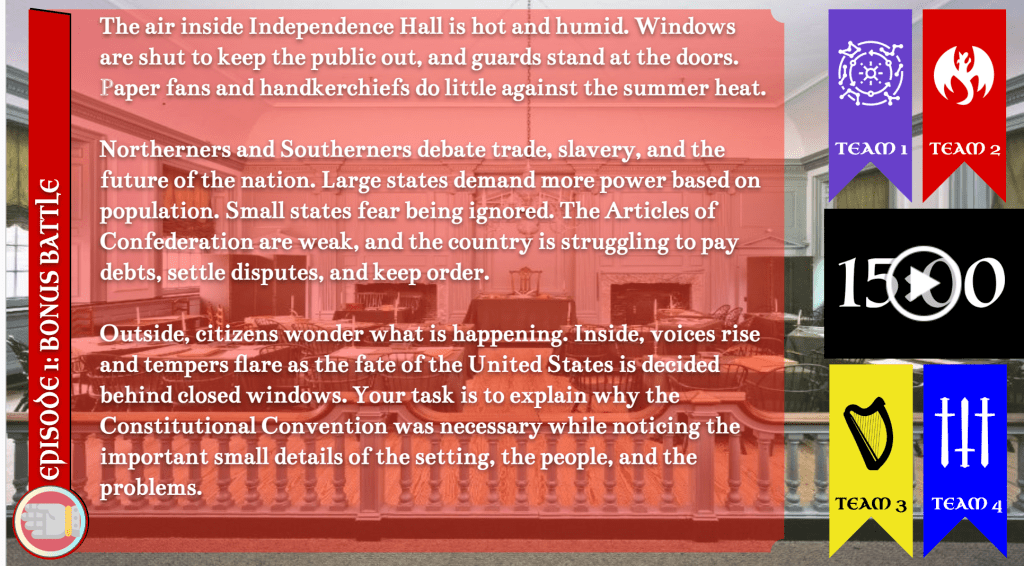

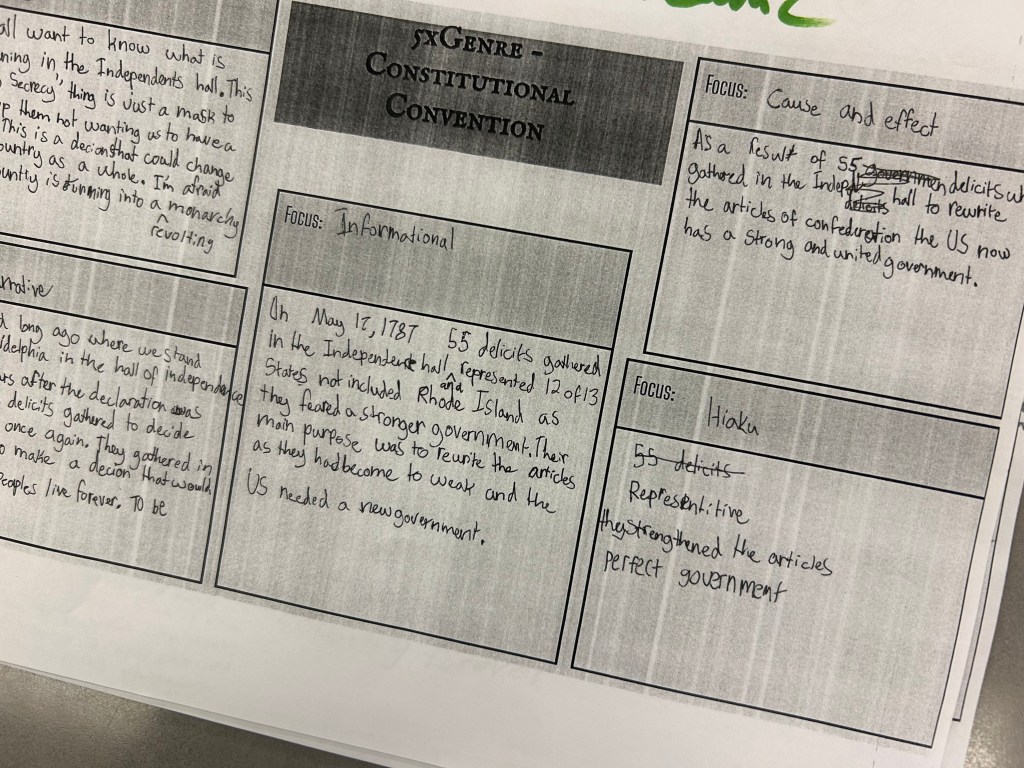

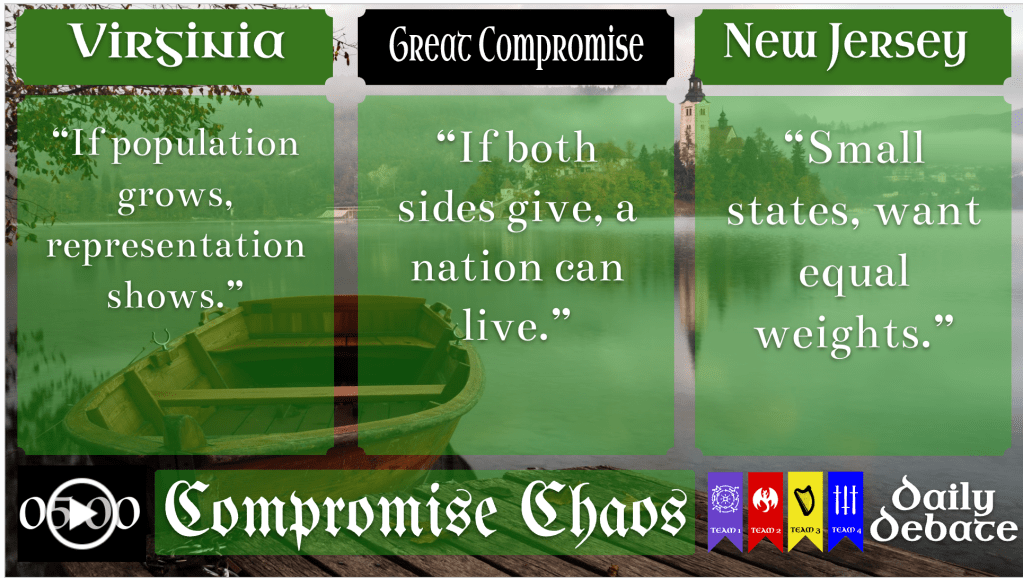

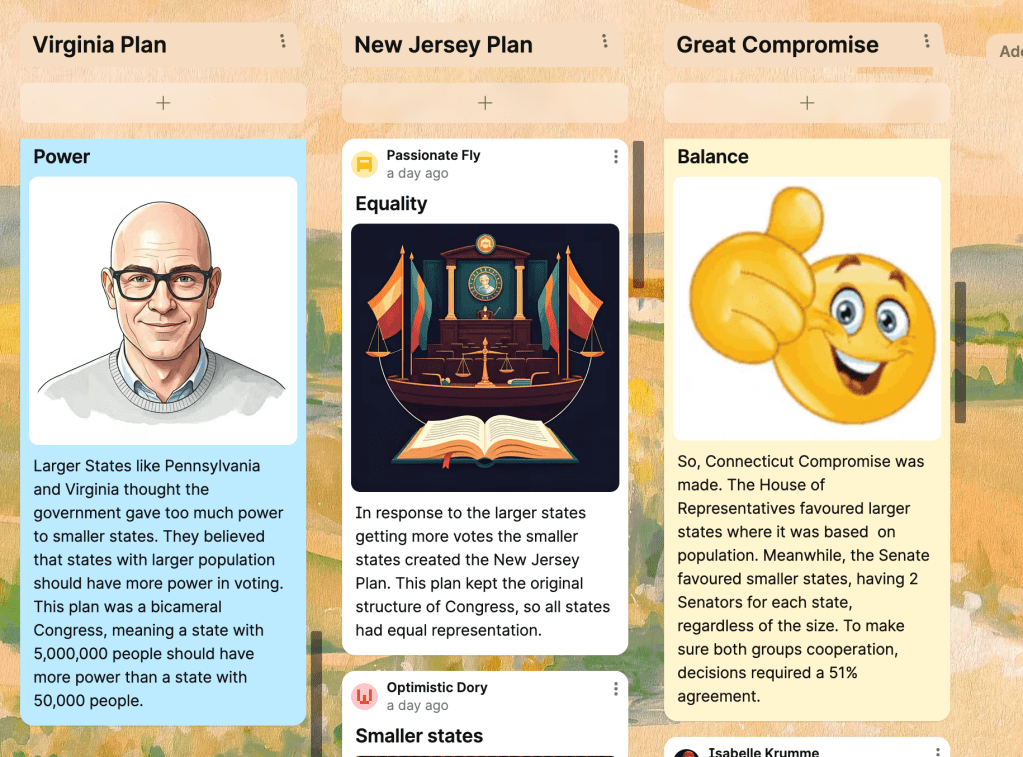

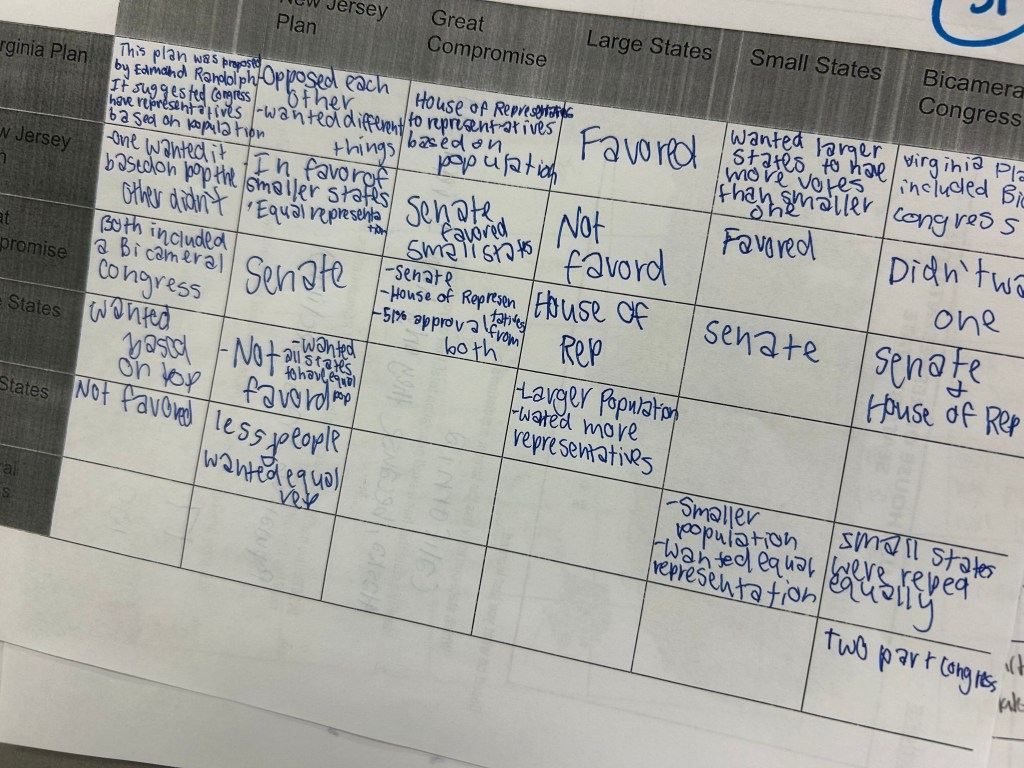

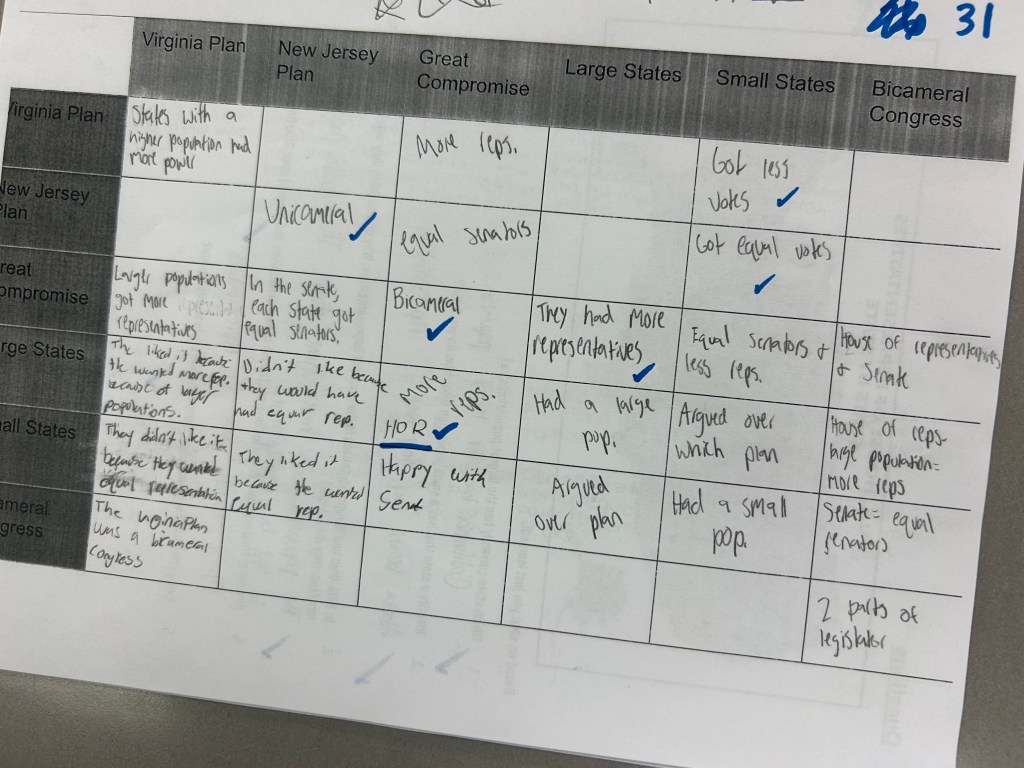

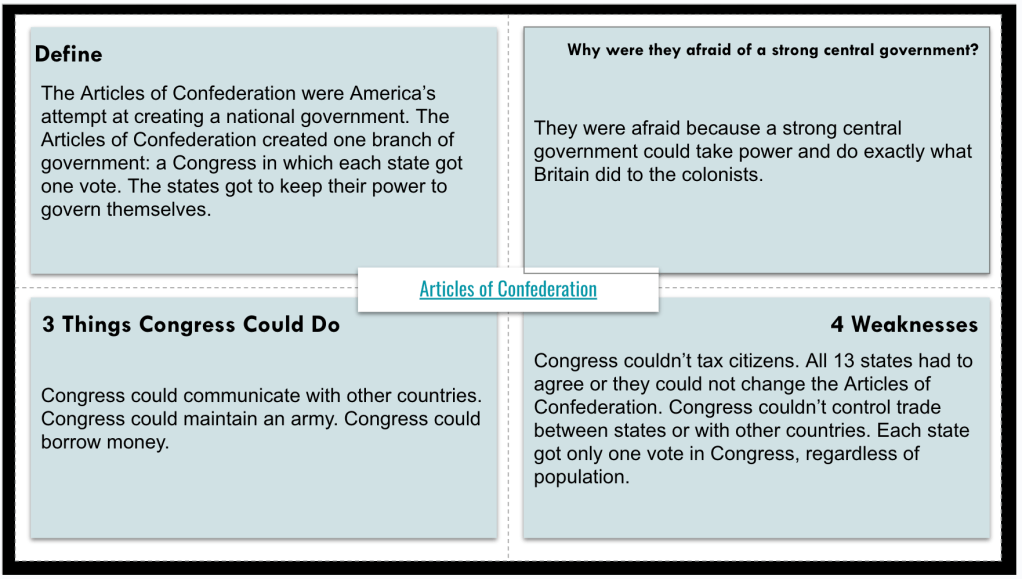

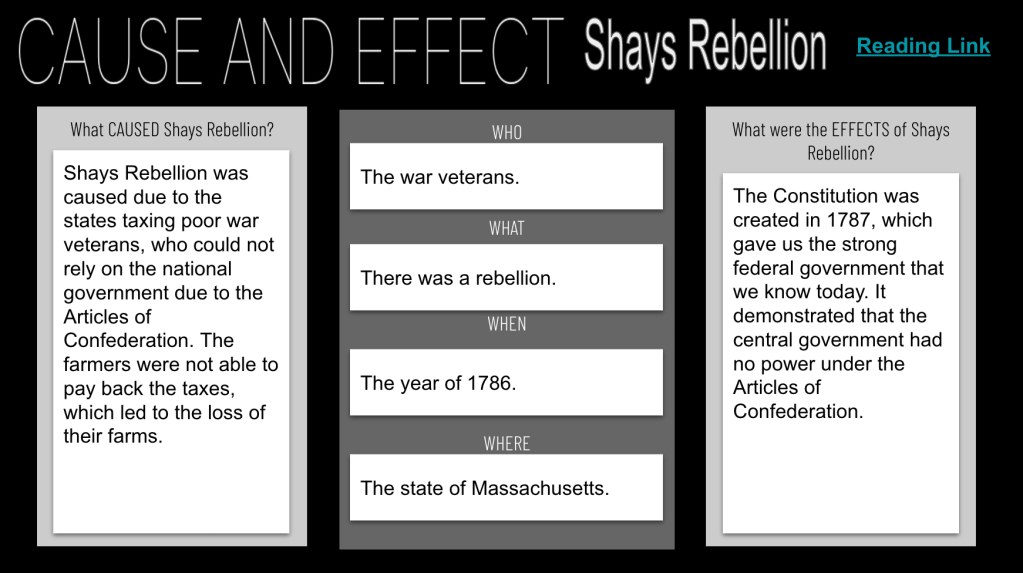

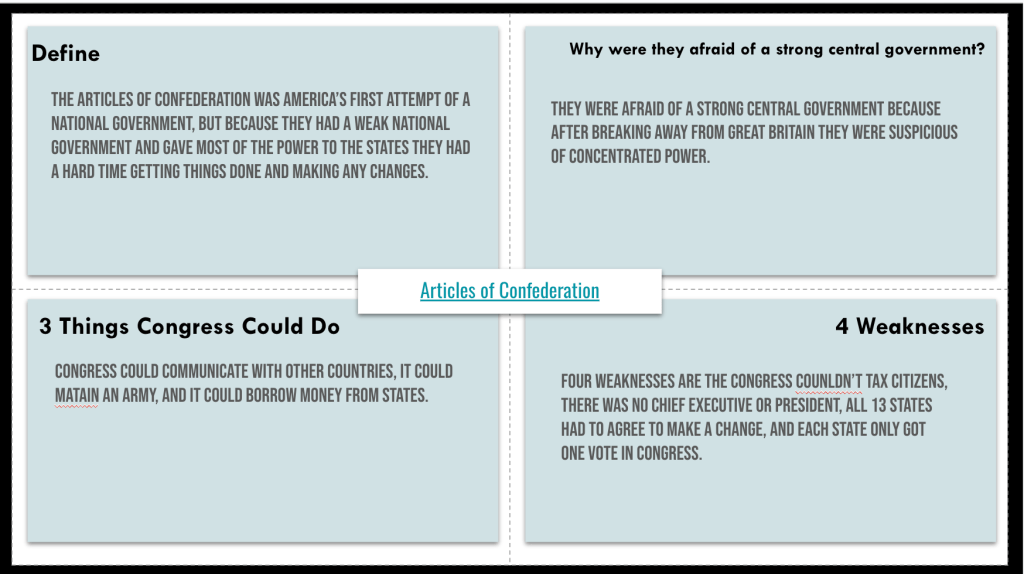

We began by looking at how the Constitution is organized. I briefly walked students through the Articles so they could see how the document is structured. We talked about how Article I reflects the Great Compromise and why Congress takes up the largest portion of the Constitution. This overview only took about five minutes, but it helps students see the Constitution as an organized framework rather than just an old document.

After that, we jumped into Quizizz for a Mastery Peak game focused on principles of government and related vocabulary. It’s a great way to check what sticks and what doesn’t. As usual, a few terms tripped students up, so afterward we talked through memory tricks.

For example, when students struggle with federalism, I remind them that “federal” refers to the national government, and the “ism” stands for “individual states matter.” It helps the idea stick, power shared between national and state governments.

To wrap things up, students moved around the room in pairs looking at quotes and images posted on the walls. Their task was to decide which principle of government each example represented and justify their thinking to their partner. It forced them to talk through their reasoning rather than just guess.

Huge thanks to Dominic Helmstetter for sharing that activity idea with me. It’s simple, but the discussion it creates is where the real learning happens.

My Favorite Thing This Week

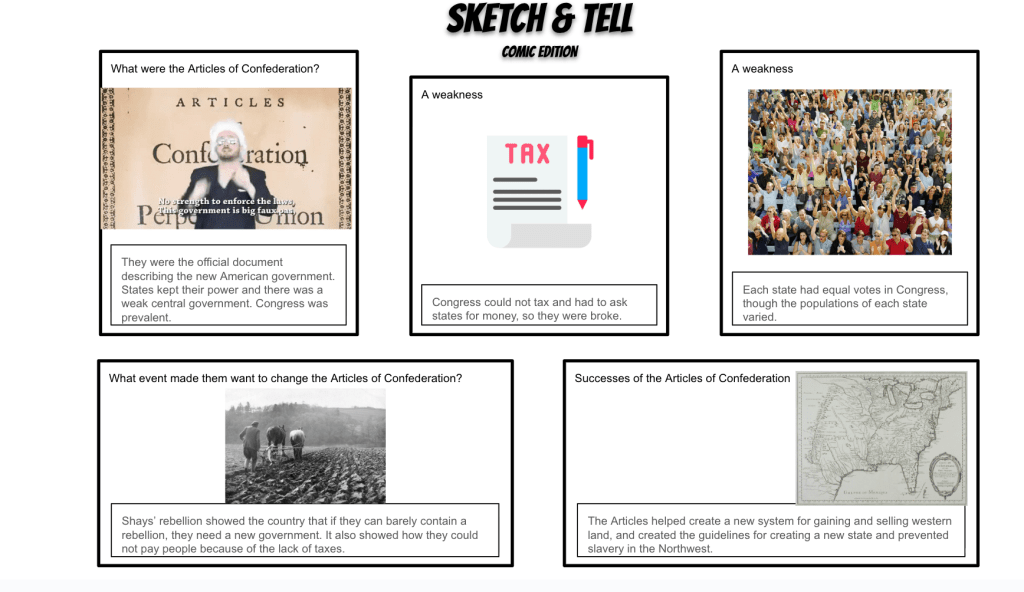

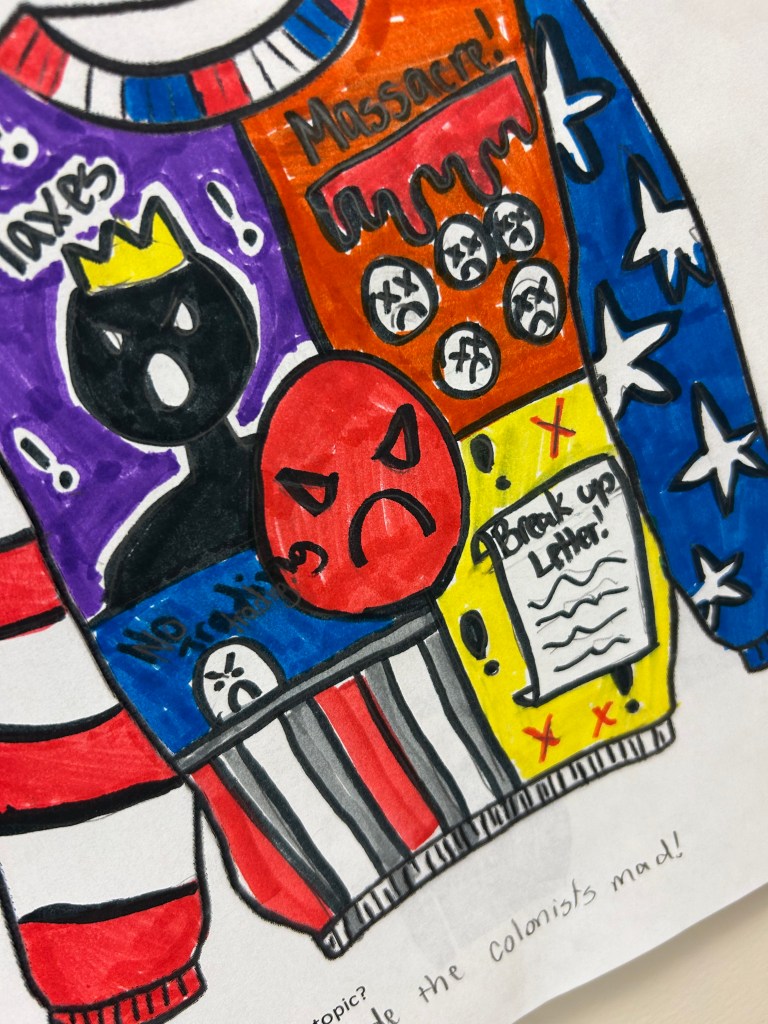

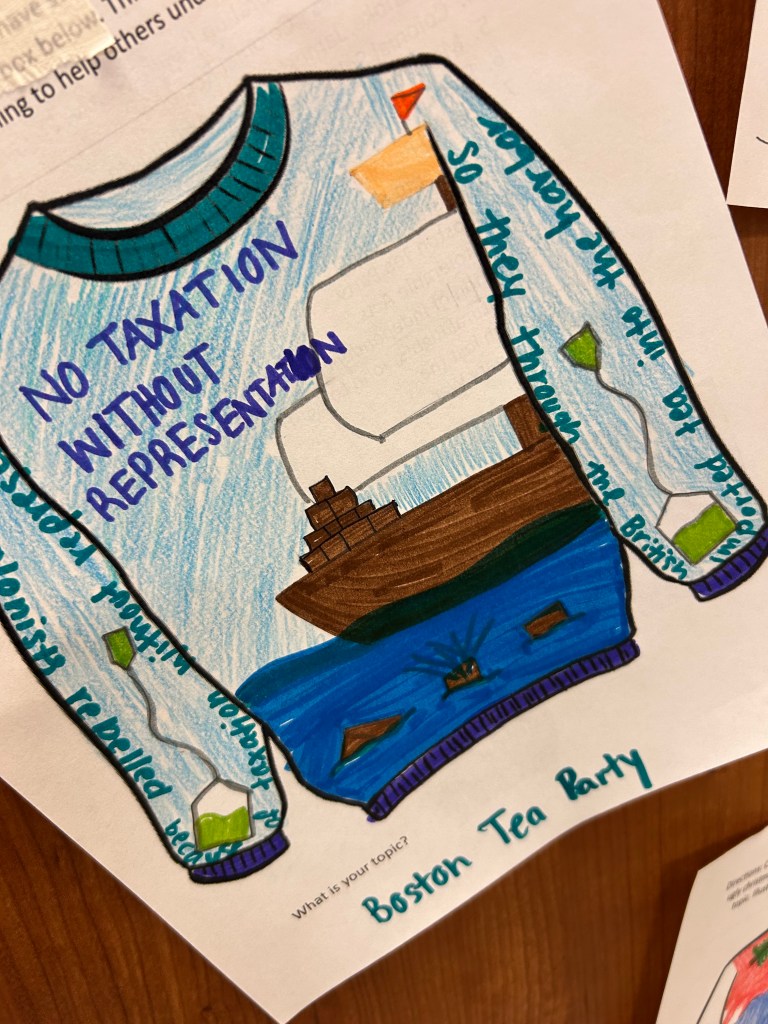

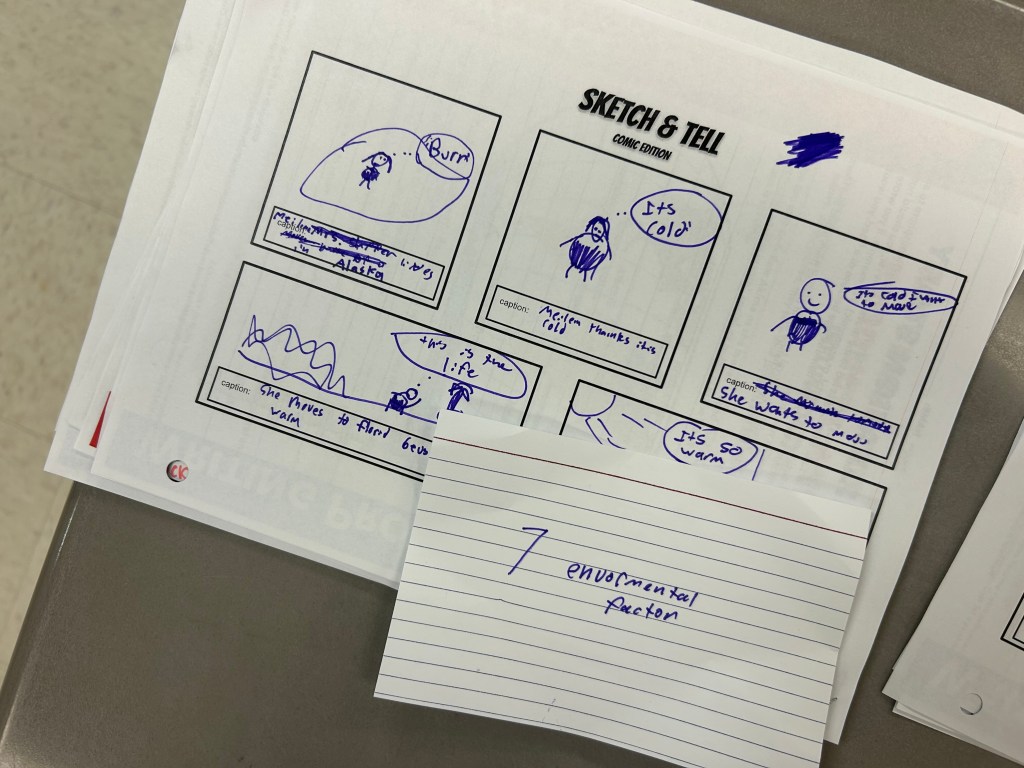

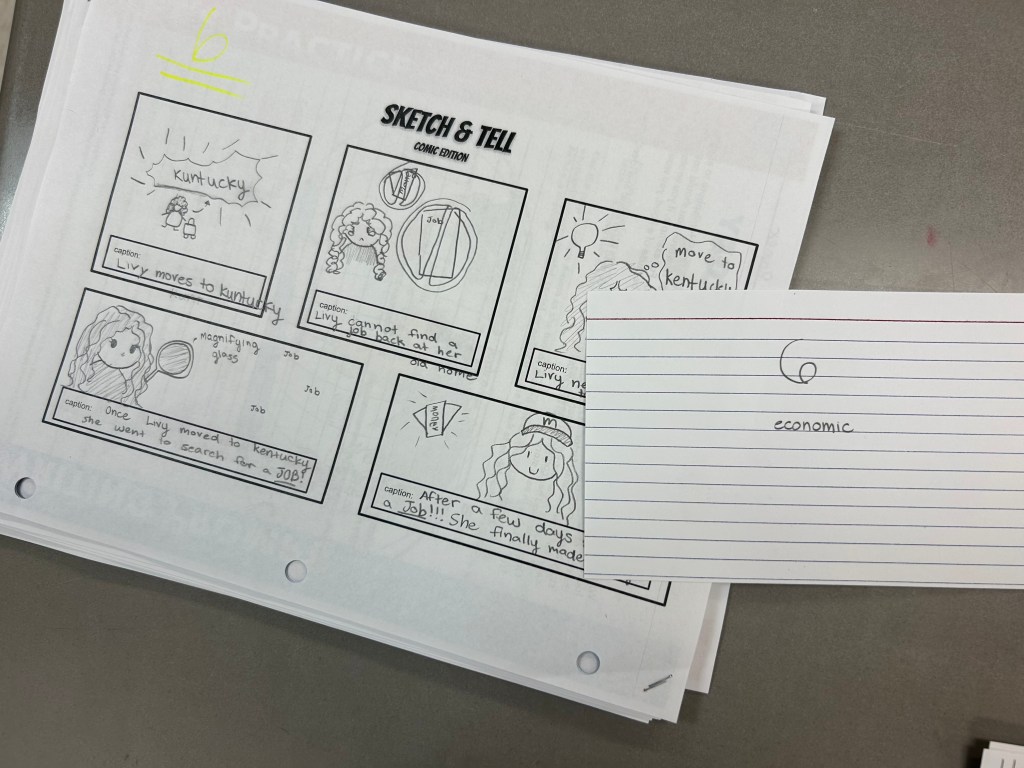

My favorite thing from the week came from my 6th grade class. Their textbook included a writing activity where students had to write a story featuring a factor that pushed someone to migrate. As I was looking at it, I immediately thought, this would make a great Sketch and Tell comic instead of just another paragraph.

The activity also asked students to trade stories and guess which migration factor was being described, political, environmental, economic, or social. That got me thinking this would also make a Great American Race style activity.

So instead, I had students create a comic, place a number at the top of their paper, and privately tell me which factor they used. On Monday, I’m going to copy them all, put them in order, and have students rotate through them in a Great American Race format where they read each story and try to identify the migration factor.

I’m sharing this in hopes it helps others think about how activities like this could work in both American history and world history classes. Sometimes the best tweaks are just small shifts that turn a writing task into something more creative and interactive.

One Last Thing

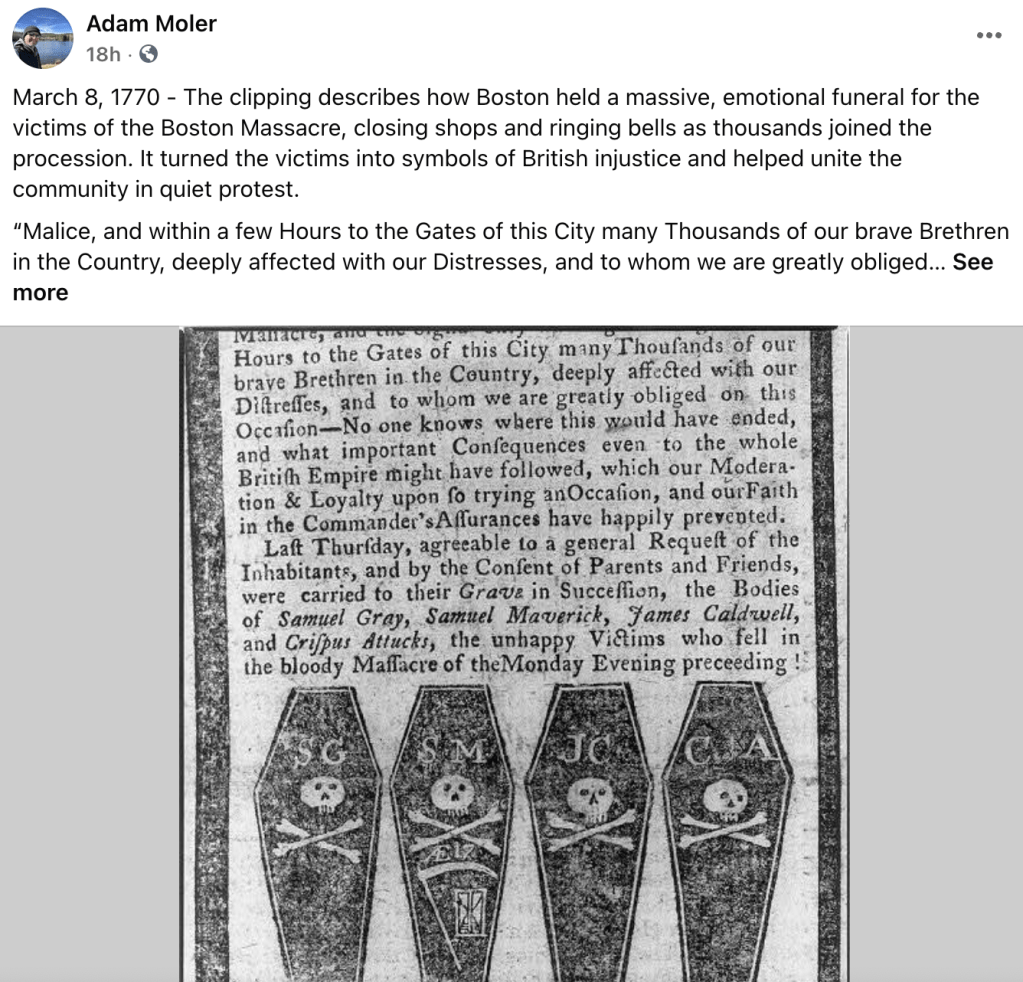

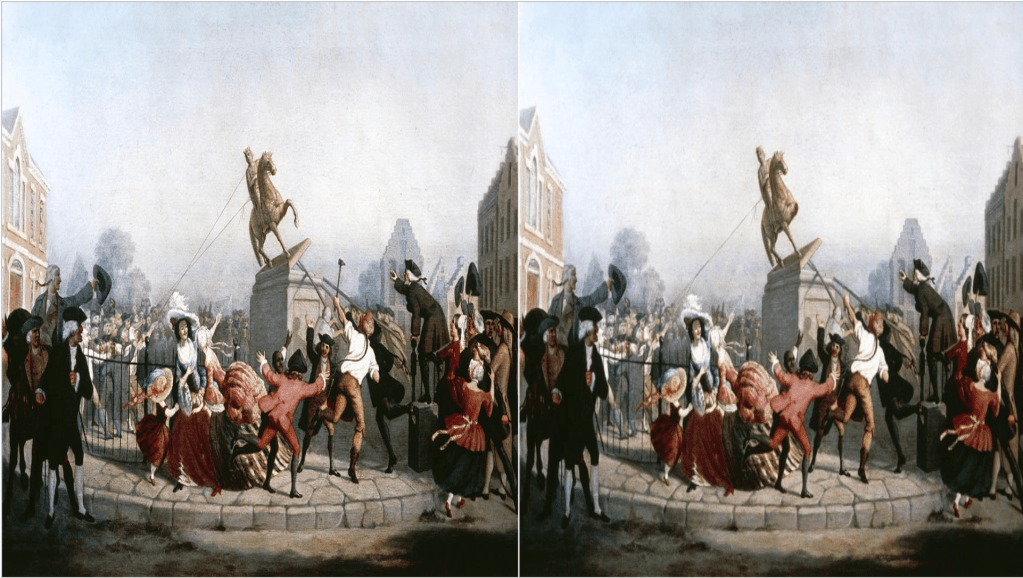

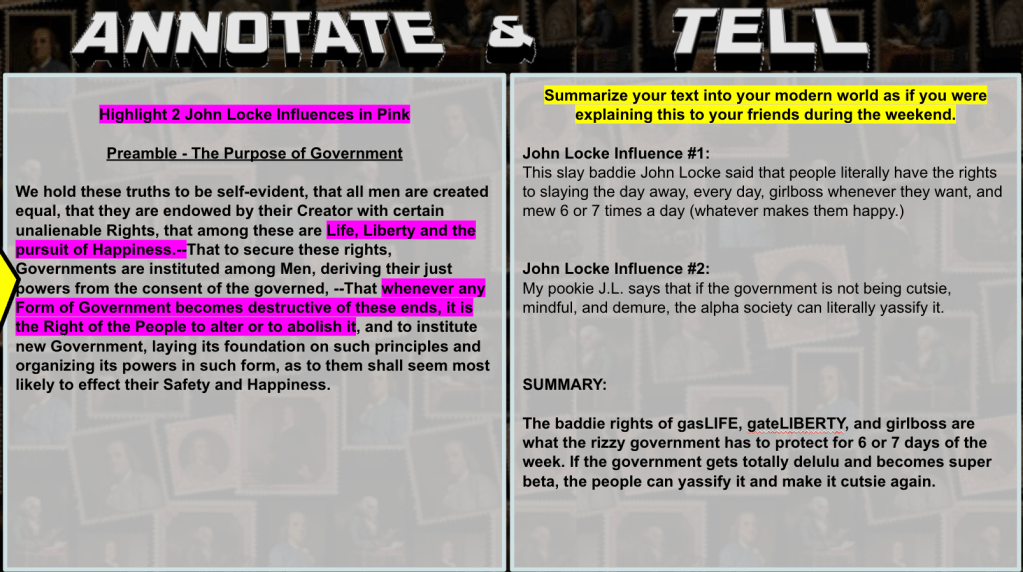

I’ve been posting a lot of quotes on Facebook lately. Part of the answer is simple. America’s 250th birthday is right around the corner, and it feels like a good time to revisit the voices that shaped the country in the first place.

But honestly, it goes deeper than that. We are so far removed from the founding of this country that many of the founders’ actual words have faded into the background. Most people recognize lines like “Give me liberty, or give me death,” or “All men are created equal,” or “We the People.” But beyond those familiar phrases, so much of the thinking, debate, and warning contained in their writings are forgotten.

Social studies often gets squeezed in schools, and when that happens, the ideas and discussions that helped shape the nation get reduced to quick sound bites (or nonexistent) instead of real reflection. We sometimes accept simplified versions of history instead of wrestling with the real meaning behind the country’s founding ideals.

And to make things even messier, plenty of quotes floating around online were never even said by the people they’re attributed to. So part of what I’m trying to do is share real words, from real documents, written by the people who were actually there.

So I’m going to keep posting them. I’m committed. I’m locked in.

It’s not political. It’s to get people thinking. And honestly, if a quote makes someone uncomfortable or frustrated, I think the better question is, why? These are the actual words of the founders and framers. Sometimes there’s a lot of irony in reading them today, but they’re still worth wrestling with.

At the end of the day, getting people to pause and think about where the country started and what those ideals meant is part of the job. And maybe, just maybe, it helps us think a little more carefully about where we’re headed too.